What Is Variceal Bleeding?

Variceal bleeding happens when swollen veins in the esophagus or stomach rupture, causing dangerous internal bleeding. These veins, called varices, form because of high pressure in the portal vein-the main blood vessel that carries blood from the intestines to the liver. When the liver is damaged by cirrhosis, it can’t process blood properly. That forces blood to find other paths, stretching thin-walled veins until they burst.

This isn’t a slow-developing problem. Once a varix starts bleeding, the risk of death within six weeks is 15% to 20%. It’s one of the deadliest complications of liver disease. Most people who experience it already have advanced cirrhosis. Many don’t know they’re at risk until they’re rushed to the ER with vomiting blood or passing dark, tarry stools.

Why Endoscopic Banding Is the Gold Standard

When someone shows up in the emergency room with active bleeding from varices, time is everything. The current standard is endoscopic band ligation (EBL)-a procedure where a doctor uses a special endoscope to place tiny rubber bands around the bleeding veins. The bands cut off blood flow, causing the veins to shrink and scar over.

It’s not just effective-it’s fast. Studies show that EBL stops bleeding in 90% to 95% of cases when done within 12 hours of admission. That’s why hospitals now treat it like a code: gastroenterology teams are paged immediately, and the procedure is scheduled before the patient even reaches the ICU. Older methods like sclerotherapy (injecting chemicals into veins) have been phased out because they cause more complications, like strictures and infections.

Modern banding devices can place up to eight bands in one session, cutting procedure time by 35% compared to older single-band tools. Most patients need three to four sessions, spaced one to two weeks apart, to fully eliminate the varices. While the procedure can cause temporary throat pain or difficulty swallowing for up to two weeks, the trade-off is clear: it saves lives.

How Beta-Blockers Prevent Bleeding Before It Starts

Not everyone with varices bleeds right away. But if you’ve had even one episode, your chances of bleeding again are over 70% in the next year. That’s where non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs) come in. These drugs-like propranolol and carvedilol-lower the pressure in the portal vein by slowing the heart and reducing blood flow to the liver.

Carvedilol is now preferred over propranolol in many cases because it reduces portal pressure more effectively-about 22% compared to 15%. Both cut the risk of rebleeding by half. But they’re not for everyone. Patients with asthma, very low heart rates, or heart failure can’t take them. Side effects like fatigue, dizziness, and low blood pressure are common. In fact, about one in three people can’t tolerate the full dose.

Doctors don’t just prescribe these drugs and walk away. They monitor the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) to make sure the medication is working. The goal? Lower the pressure to under 12 mmHg, or reduce it by at least 20% from baseline. If they don’t hit that target, the drug dose is adjusted. Many patients struggle with adherence-especially because generic propranolol costs as little as $4 a month, but branded carvedilol can run $25 to $40. For those on fixed incomes, that’s a real barrier.

When Banding Alone Isn’t Enough

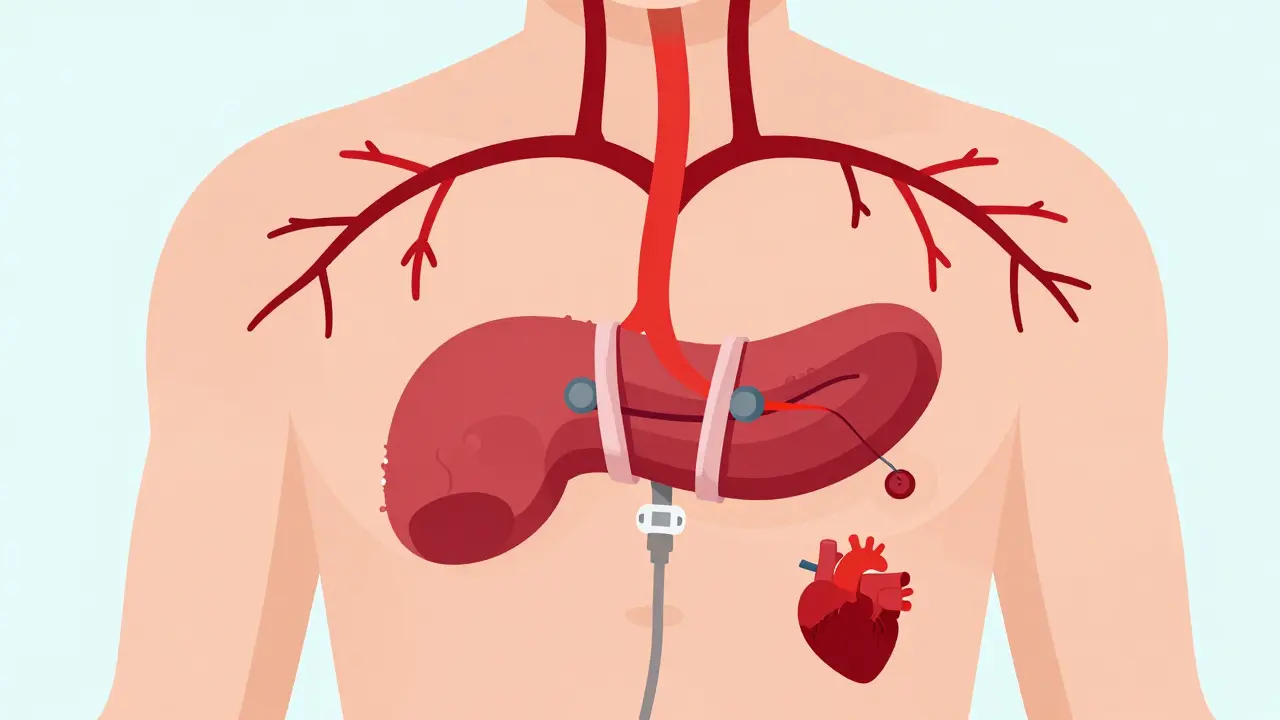

Not all varices are the same. Those in the stomach (gastric varices) don’t respond as well to banding as those in the esophagus. For these, doctors often turn to balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO). This procedure involves threading a catheter through a vein in the leg, inflating a balloon to block blood flow, and injecting a glue-like substance to seal the varix. Studies show BRTO cuts 30-day mortality nearly in half compared to banding alone for gastric varices.

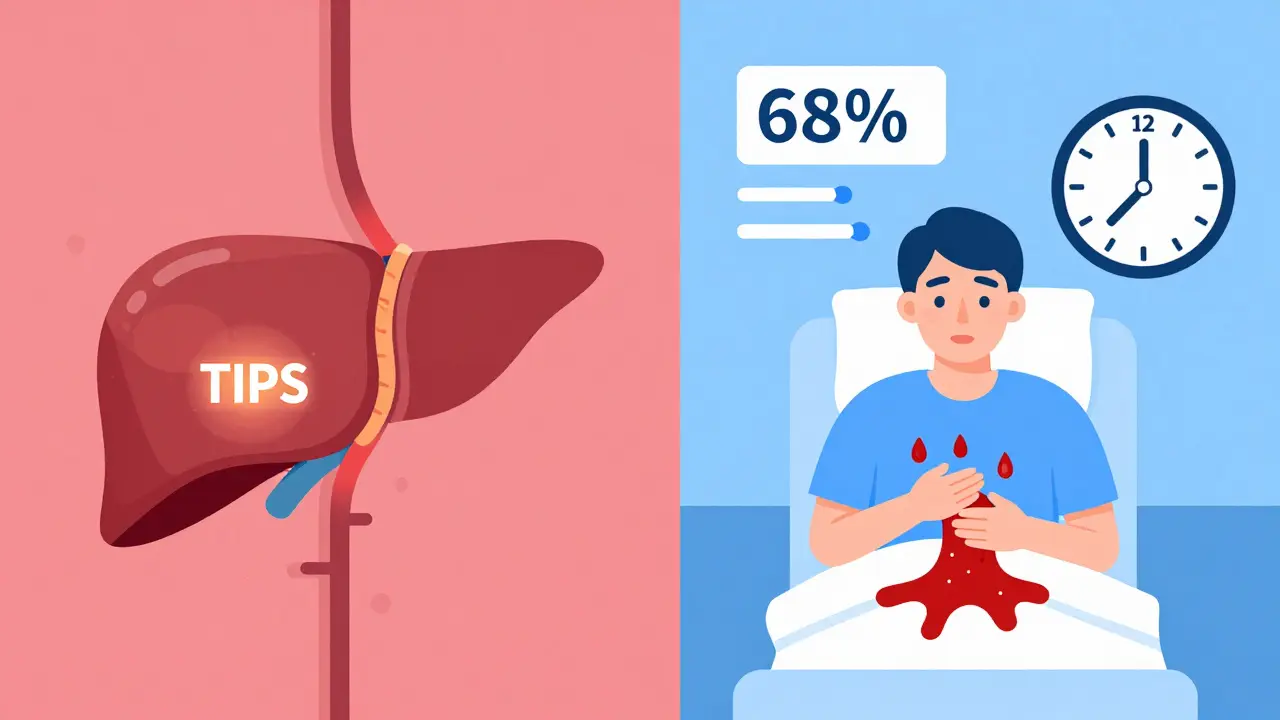

For the highest-risk patients-those with Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis and active bleeding-transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is the most powerful tool. TIPS creates a permanent tunnel inside the liver that diverts blood away from the portal vein. It reduces rebleeding rates dramatically. One major study showed 86% of TIPS patients survived a year, compared to just 61% with standard care.

But TIPS isn’t perfect. About 30% of patients develop hepatic encephalopathy-a brain condition caused by toxins building up when blood bypasses the liver. And not every hospital can do it. Only 45% of U.S. hospitals have interventional radiologists trained and available to perform TIPS within 24 hours. That’s why timing matters. Some experts argue for early TIPS within 72 hours for high-risk patients. Others say it’s too risky without enough expertise on hand.

The Real-World Challenges Patients Face

Guidelines look clean on paper. In real life, things get messy. A 2023 survey found that only 68% of patients got an endoscopy within the critical 12-hour window. And only 55% of those on beta-blockers reached the full therapeutic dose within three months. Why? Delays in scheduling, lack of specialist access, and patient side effects.

Patients on Reddit and health forums talk about the emotional toll. One person wrote: "I dread the banding appointments every two weeks, but I know it’s saving my life." Another said propranolol left them too tired to get out of bed. Cost is another issue-carvedilol’s $35 monthly copay is unaffordable for some, even with insurance.

Even with perfect treatment, 65% of patients still have at least one rebleeding episode within a year. That’s why prevention doesn’t end with banding or pills. It means avoiding alcohol, getting vaccinated for hepatitis, managing diet, and seeing specialists regularly. Many patients fall through the cracks because they don’t have access to nurse navigators or liver disease support programs.

What’s Coming Next

The field is evolving fast. In 2023, the FDA approved a new monthly injection form of octreotide (Sandostatin LAR), which could improve adherence for patients who struggle with daily shots. Researchers are also testing whether carvedilol alone can replace banding for primary prevention in high-risk patients-not just prevent rebleeding, but stop bleeding from ever happening.

Future tools include AI systems that predict bleeding risk by analyzing lab values, imaging, and patient history. One study suggests these systems could cut mortality by 40% in the next decade. Another promising approach is percutaneous transsplenic TIPS, which could make the procedure available in 75% of U.S. hospitals by 2027 instead of just 45%.

But progress won’t mean much without equity. Uninsured patients die from variceal bleeding at 35% higher rates than those with insurance. Better treatments won’t help if people can’t get to the doctor, afford meds, or find a specialist nearby.

What You Need to Know If You or a Loved One Is Affected

- If you have cirrhosis, get screened for varices with an endoscopy-even if you feel fine.

- If you’ve had bleeding, you’ll need both banding and beta-blockers. Don’t skip either.

- Carvedilol may work better than propranolol, but talk to your doctor about cost and side effects.

- Don’t wait for symptoms. If you vomit blood, pass black stools, or feel dizzy and weak, go to the ER immediately.

- Ask about nurse navigator programs through the American Liver Foundation-they help coordinate care and find financial aid.

- Alcohol is the biggest trigger for worsening liver disease. Quitting is the single most effective way to prevent varices from forming or bleeding.

Post A Comment