Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) isn't just another form of Parkinson’s disease. It’s a far more aggressive, less predictable, and ultimately deadlier neurodegenerative disorder that steals movement, balance, and even basic bodily functions-often before most people realize what’s happening. While Parkinson’s disease affects about 1 million Americans, MSA strikes only about 1 in 100,000 people each year. But for those it does affect, the decline is rapid, relentless, and largely untreatable.

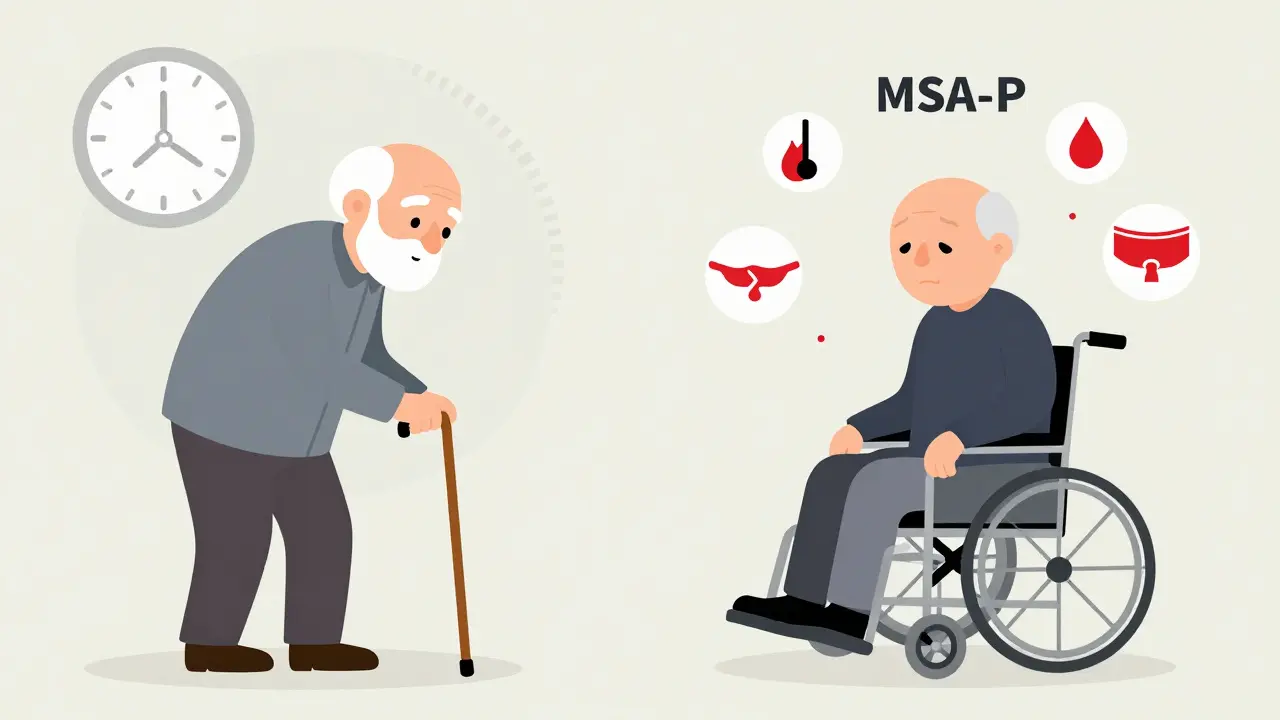

What Makes MSA-P Different from Parkinson’s?

The parkinsonian subtype, known as MSA-P, makes up 65-70% of all MSA cases. At first glance, it looks like Parkinson’s: slow movements, stiff muscles, trouble walking, and a soft, slurred voice. But the similarities end there. People with MSA-P don’t respond well to levodopa-the main drug used for Parkinson’s. Only 15-30% see any benefit, and even then, it lasts less than two years. That’s a major red flag.

Another key difference? Tremors. In Parkinson’s, tremors usually happen at rest-a hand shaking when it’s resting in your lap. In MSA-P, tremors are jerky and appear mostly when holding a position, like reaching for a cup. They’re not the classic ‘pill-rolling’ tremor. Instead, they’re more like a sudden, uncontrolled jerk.

And then there’s the face. MSA-P often causes a mask-like expression, staring eyes, and trouble swallowing. Speech becomes quiet, breathy, or quivering. Chewing becomes a chore. These aren’t minor annoyances-they’re early signs of nerve cells dying in the brainstem, the area that controls basic life functions.

The Silent Killer: Autonomic Failure

What truly separates MSA from Parkinson’s isn’t just how you move-it’s how your body fails to regulate itself. Autonomic dysfunction is the hallmark of MSA. This isn’t just occasional dizziness. It’s a complete breakdown of the system that keeps your blood pressure, heart rate, bladder, and digestion running.

Ninety percent of MSA-P patients have orthostatic hypotension-a dangerous drop in blood pressure when standing up. This isn’t just feeling lightheaded. It’s fainting, falling, and sometimes hitting your head on the floor. One patient described it as ‘walking into a wall without realizing it.’

Bladder problems hit 85-90% of people. Urgency, incontinence, or being unable to empty the bladder at all. For men, erectile dysfunction often shows up years before any movement issues. It’s one of the earliest clues doctors miss because they’re focused on walking or shaking.

Sleep is another battleground. Eighty to ninety percent of MSA-P patients act out their dreams-kicking, yelling, even falling out of bed. That’s REM sleep behavior disorder. Add in sleep apnea, which affects 60-70%, and you’ve got a person who’s exhausted before they even get out of bed.

Temperature control fails too. Some lose the ability to sweat on their arms or legs, while others overheat without cause. It’s like the body’s thermostat is broken.

How Fast Does It Progress?

Time is the enemy in MSA-P. The median age of onset is 54. Most people are diagnosed in their early 60s. But by then, the damage is already widespread.

Within 1-2 years of symptom start, 85% of MSA-P patients have already had at least one fall. By 3.5 years, most need a cane or walker. By 5.3 years, they’re in a wheelchair. Five years after diagnosis, half of all MSA-P patients have lost nearly all their motor skills.

Survival is grim. The median life expectancy from symptom onset is 6-10 years. Only about half live past 5 years. After 10 years, fewer than one in five are still alive. The most common causes of death? Aspiration pneumonia from swallowing problems, respiratory infections, and sudden cardiac arrest.

Compare that to Parkinson’s: many live 15-20 years after diagnosis with reasonable quality of life. MSA-P doesn’t give you that time.

Why Is Diagnosis So Hard?

Doctors often mistake MSA-P for Parkinson’s-especially in the first year. The symptoms overlap too much. That’s why diagnostic accuracy only hits 85-90% after 3-5 years.

But there are clues. If autonomic symptoms show up within three years of movement problems, it’s almost certainly MSA. A brain MRI might show the ‘hot cross bun’ sign-a cross-shaped pattern in the brainstem that’s seen in 50-80% of MSA-C cases and sometimes in MSA-P. Putaminal atrophy (shrinkage in a part of the basal ganglia) is another telltale sign.

Even blood tests are starting to help. Levels of neurofilament light chain-a protein that leaks out when nerve cells die-are 3-5 times higher in MSA than in Parkinson’s. This could soon become a routine test to confirm diagnosis early.

What Treatments Actually Help?

There is no cure. No drug slows or stops MSA. Treatment is all about managing symptoms and trying to keep people safe and comfortable.

For low blood pressure, doctors prescribe midodrine, fludrocortisone, or droxidopa. These help you stand without passing out-but they don’t fix the underlying nerve damage. For bladder issues, catheters, anticholinergics, or botox injections may be used. Sleep apnea gets treated with CPAP machines. Physical therapy helps maintain mobility as long as possible. Speech therapy can teach safer swallowing techniques.

Levodopa is still tried-usually at high doses for 3-6 months. But if there’s no clear improvement in that time, it’s stopped. Continuing it doesn’t help and just adds side effects.

There are no new drugs on the horizon. Clinical trials targeting the toxic alpha-synuclein protein-like the PASADENA trial-showed almost no benefit. The most promising research now focuses on early detection. A panel combining MRI scans, blood biomarkers, and autonomic tests could diagnose MSA within a year of symptoms starting. That’s critical. By the time movement problems appear, half the nerve cells are already gone.

Living With MSA-P: The Human Cost

Patients describe it as a slow, silent unraveling. One man diagnosed at 52 said, ‘I needed a cane in 18 months. A walker by 3 years. A wheelchair by 4.’ Another, age 55, said, ‘My neurologist said most don’t live past 8 years. That’s devastating.’

A 2021 survey of 327 MSA patients found that 78% rated their quality of life as ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ within four years of diagnosis. In Parkinson’s, that number is only 35% at the same stage.

It’s not just the physical decline. It’s the isolation. The loss of independence. The guilt of being a burden. The fear of choking at dinner or collapsing in the shower. Families struggle to keep up. Caregivers burn out. Support systems are thin-there are only three active clinical trials worldwide targeting disease modification as of late 2023.

There’s no hope for a cure soon. But early recognition, aggressive symptom management, and compassionate care can make those last years more bearable.

What’s Next for MSA Research?

Researchers are racing to find biomarkers that catch MSA before it’s too late. The European MSA Study Group is validating a test that combines MRI changes, blood neurofilament levels, and autonomic function scores. If it works, diagnosis could happen within a year-giving patients a chance to plan, enroll in trials, or access supportive care sooner.

But without a breakthrough in understanding how alpha-synuclein kills nerve cells, progress will be slow. The MSA Coalition’s 2023 report is blunt: ‘Without significant breakthroughs in understanding MSA’s pathogenesis, the prognosis for MSA-P will remain poor, with median survival unlikely to extend beyond 10 years in the next decade.’

For now, the focus remains on dignity, safety, and comfort. Because in MSA-P, time doesn’t just run out-it runs away fast.

Is Multiple System Atrophy the same as Parkinson’s disease?

No, MSA is not the same as Parkinson’s disease. While both cause movement problems like stiffness and slowness, MSA is more aggressive and affects more parts of the brain. It includes severe autonomic failure-like dangerous drops in blood pressure, bladder control loss, and sleep disorders-that rarely appear this early in Parkinson’s. MSA also responds poorly to levodopa, while Parkinson’s patients often see long-term improvement. The underlying brain damage and progression speed are very different.

How long do people with MSA-P typically live after diagnosis?

The median survival time from symptom onset is 6 to 10 years. About half of people with MSA-P live past 5 years, and only 9-23% survive beyond 10 years. The disease progresses faster than Parkinson’s, with most patients becoming wheelchair-dependent within 5 years and facing life-threatening complications like aspiration pneumonia or sudden cardiac death.

Can MSA-P be cured or slowed down?

There is currently no cure for MSA-P, and no treatment has been proven to slow its progression. Medications like levodopa may help a small number of patients temporarily, but the benefit is usually short-lived. Current care focuses on managing symptoms-like low blood pressure, bladder issues, and sleep problems-to improve comfort and safety. Research into disease-modifying therapies is ongoing, but no breakthrough has yet succeeded in clinical trials.

What are the earliest signs of MSA-P?

Early signs often include autonomic symptoms that appear before movement problems: dizziness or fainting when standing (orthostatic hypotension), urinary urgency or incontinence, erectile dysfunction in men, and acting out dreams during sleep (REM sleep behavior disorder). These can show up years before stiffness, slowness, or balance issues. When these symptoms appear together, especially in someone over 50, MSA-P should be considered.

Why is MSA-P so hard to diagnose early?

MSA-P mimics Parkinson’s disease in its early stages, making it easy to misdiagnose. Symptoms like slow movement and stiffness are common to both. Autonomic symptoms may be dismissed as unrelated or age-related. Even with advanced imaging, diagnostic accuracy only reaches 85-90% after 3-5 years. New biomarkers-like elevated neurofilament light chain in blood and specific MRI patterns-are helping, but they’re not yet widely available in routine care.

Post A Comment