When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, you’d think generic versions would flood the market right away. But that’s rarely what happens. In reality, it can take years after patent expiration before a generic version actually hits pharmacy shelves. Why? It’s not just about waiting for the clock to run out. There’s a whole system of legal, regulatory, and business hurdles designed to delay competition - even when the law says it should be allowed.

Patents Aren’t the Whole Story

Most people think pharmaceutical patents last 20 years. That’s technically true - the patent clock starts ticking from the day the application is filed. But here’s the catch: drug development takes 8 to 10 years before it even gets to market. So by the time a new drug is approved and sold, it’s already lost half its patent life. That leaves only 7 to 12 years of real market exclusivity. Companies don’t just rely on this single patent. They layer on others: patents for the active ingredient, for the pill’s coating, for how it’s made, even for how it’s used to treat a specific condition. The average drug in the FDA’s Orange Book has 14.2 patents listed. That’s not innovation - it’s a legal fence.The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Deal With Teeth

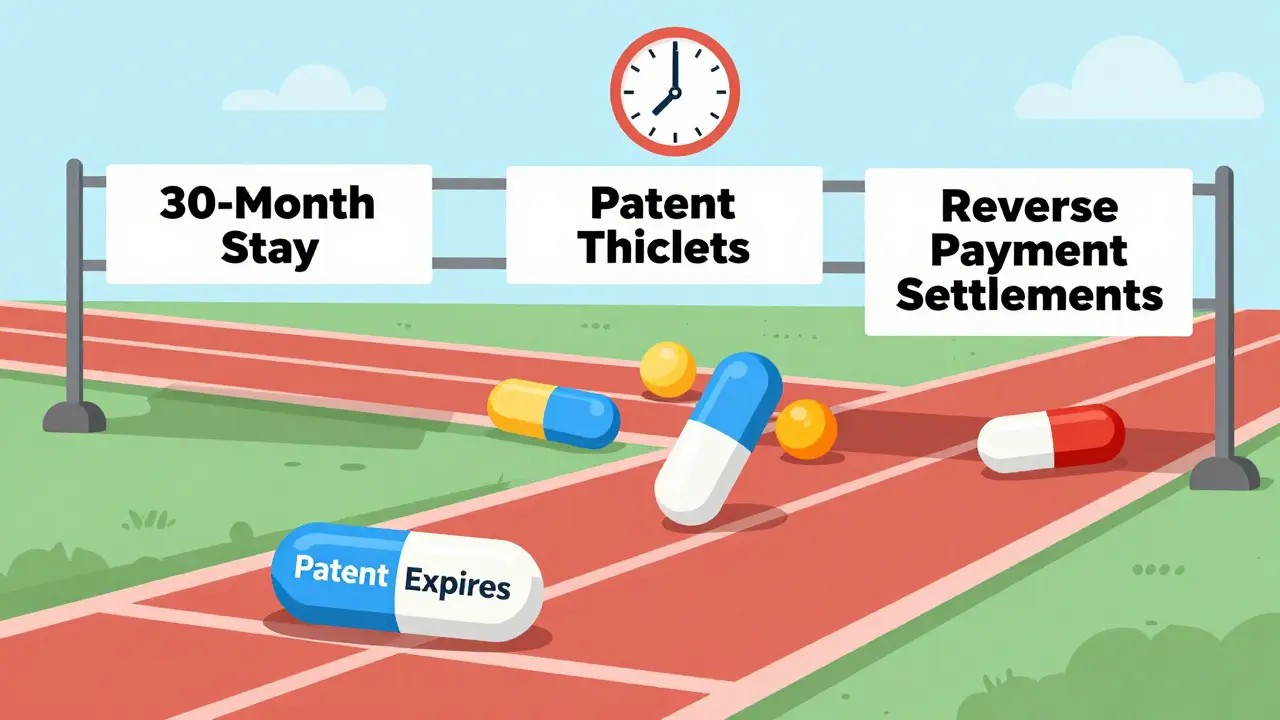

In 1984, Congress passed the Hatch-Waxman Act to balance innovation and access. It created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This lets generic makers prove their drug works the same as the brand-name version - without repeating expensive clinical trials. They just need to show bioequivalence: same active ingredient, same dose, same way it’s absorbed in the body. Simple, right? Not quite. The real twist is in the incentives and delays built into the system. If a generic company files an ANDA and says, “Our drug doesn’t infringe on your patent,” that’s called a Paragraph IV certification. The brand-name company then has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months - a legal pause called the 30-month stay. But here’s what most don’t realize: the 30-month stay rarely causes the biggest delays. Studies show that even after this period ends, generics still take an average of 3.2 more years to actually launch. Why? Because the real bottleneck isn’t the court system - it’s the patent thickets.Patent Thickets and the 180-Day Race

When a generic company successfully challenges a patent, they get a 180-day exclusivity period. That means no other generic can enter the market during that time. It’s a huge reward - and a huge pressure cooker. The first filer has to launch within 75 days of FDA approval, or they lose it. That’s why many rush production, sometimes cutting corners. In 2022, 22% of first filers forfeited their exclusivity because they couldn’t get their manufacturing right in time. Another 10% lost it because of court rulings. Meanwhile, other generic makers sit back. Why? Because if the first filer delays, they can wait for the exclusivity period to expire - then jump in with no competition. This creates a game of chicken. Sometimes, brand-name companies even pay generic firms to delay - known as “reverse payment” settlements. The FTC found these cost consumers $3.5 billion a year. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled these deals could violate antitrust laws, but they haven’t disappeared. In fact, 55% of delayed generic entries still trace back to these settlements.

Why Some Drugs Take Longer Than Others

Not all drugs are created equal. Simple, small-molecule pills - like blood pressure or cholesterol meds - usually see generics within 1.5 years of patent expiration. But complex drugs? They’re a different story. Biologics, like insulin or rheumatoid arthritis treatments, aren’t even eligible for traditional generics. They need biosimilars, which follow a whole different approval path under the BPCIA. These take an average of 4.7 years to enter the market. Even within small molecules, some face longer delays. Cardiovascular drugs, for example, average 3.4 years after patent expiry before generics arrive. Dermatological drugs? Just 1.2 years. Why? It’s not about complexity alone - it’s about how many patents are stacked on top of each other. A drug with over 10 patents in the Orange Book takes 37% longer to get generic competition than one with just one.The FDA’s Role: Approval ≠ Availability

The FDA approved 1,165 generic drugs in 2021. But only 62% of them reached the market within six months of approval. Why? Because approval doesn’t mean you can sell. If there’s an active patent, or if the generic maker is stuck in litigation, they can’t legally launch. Even if the FDA says “yes,” the courts or the brand-name company can still block the door. The FDA has tried to speed things up. Under GDUFA II (implemented in 2023), they promised to review complex generics in 24 months instead of 36. But as of mid-2024, only 62% of those applications met the target. And even when they do, manufacturers still need time to scale production, secure raw materials, and set up distribution. That’s not a regulatory delay - it’s a business one.

Who Controls the Market?

The generic drug market isn’t full of small players. It’s dominated by three giants: Teva, Viatris, and Sandoz. Together, they control 45% of the $70 billion U.S. generic market. That means they have the resources to file dozens of ANDAs, challenge patents, and wait out legal battles. Smaller companies? They often can’t afford to play. That’s why a drug with high revenue - over $1 billion a year - faces an average of 17.3 patent challenges. Lower-revenue drugs? Just 8.2. The system favors deep pockets.What’s Changing? What’s Not

There are signs of progress. The CREATES Act of 2019 forced brand-name companies to provide samples to generic makers - a tactic some used to block competition. The Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020 made patent listings more accurate, cutting disputes by 32% in its first year. The FDA is also testing AI to speed up bioequivalence testing - which could cut development time by 25%. But the big problem remains: patent evergreening. Brand-name companies still file new patents on minor changes - a different tablet shape, a new coating - right after the original patent expires. A 2024 study found that 68% of brand-name drugs get at least one new patent within 18 months of the original expiration. That’s not innovation. That’s a tactic to reset the clock.The Real Cost of Delay

Generic drugs make up 92% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they account for only 16% of total drug spending. That’s how much money they save - $373 billion a year. When a generic is delayed by just one year on a top-selling drug, Medicare alone loses $1.2 billion. That’s not abstract. That’s insulin, heart meds, antidepressants - drugs millions rely on. Every month of delay means higher out-of-pocket costs for patients and higher premiums for insurers. The median time from patent expiration to generic availability? 18 months. That’s what FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said in early 2024. And despite all the laws, all the reforms, all the data - that number hasn’t moved much in a decade.So when you hear that a drug’s patent has expired, don’t assume the generic is coming soon. It might be years. And until the system stops rewarding legal delays over real competition, that’s the reality for patients, pharmacists, and payers alike.

Why don’t generic drugs appear immediately after a patent expires?

Even after a patent expires, generic manufacturers must navigate legal challenges, regulatory reviews, and manufacturing hurdles. Brand-name companies often file lawsuits to trigger a 30-month stay, delaying FDA approval. Patent thickets - multiple overlapping patents - further complicate entry. Plus, some generics are blocked by settlement deals where brand-name companies pay generics to delay launch.

What is the ANDA process?

The Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) is the FDA pathway for approving generic drugs. Instead of repeating full clinical trials, generic makers must prove their product is bioequivalent to the brand-name drug - meaning it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. This cuts costs and time, but still requires years of development and testing.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement made by a generic drug applicant that claims the brand-name drug’s patent is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for up to 30 months - a major delay tactic in the system.

Why do some generic drugs have 180-day exclusivity?

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of market exclusivity. During that time, no other generic can enter. This creates a race to file - but also a risk. If the first filer can’t launch within 75 days of approval, they lose the exclusivity. Many fail due to manufacturing delays or legal issues.

How do patent thickets delay generic entry?

Patent thickets are multiple, overlapping patents covering different aspects of a drug - its chemical structure, formulation, method of use, manufacturing process. Generic makers must challenge each one, which takes time, money, and legal effort. Drugs with more than 10 Orange Book-listed patents take 37% longer to enter the market than those with just one.