When a drug’s patent runs out, prices don’t just dip-they plummet

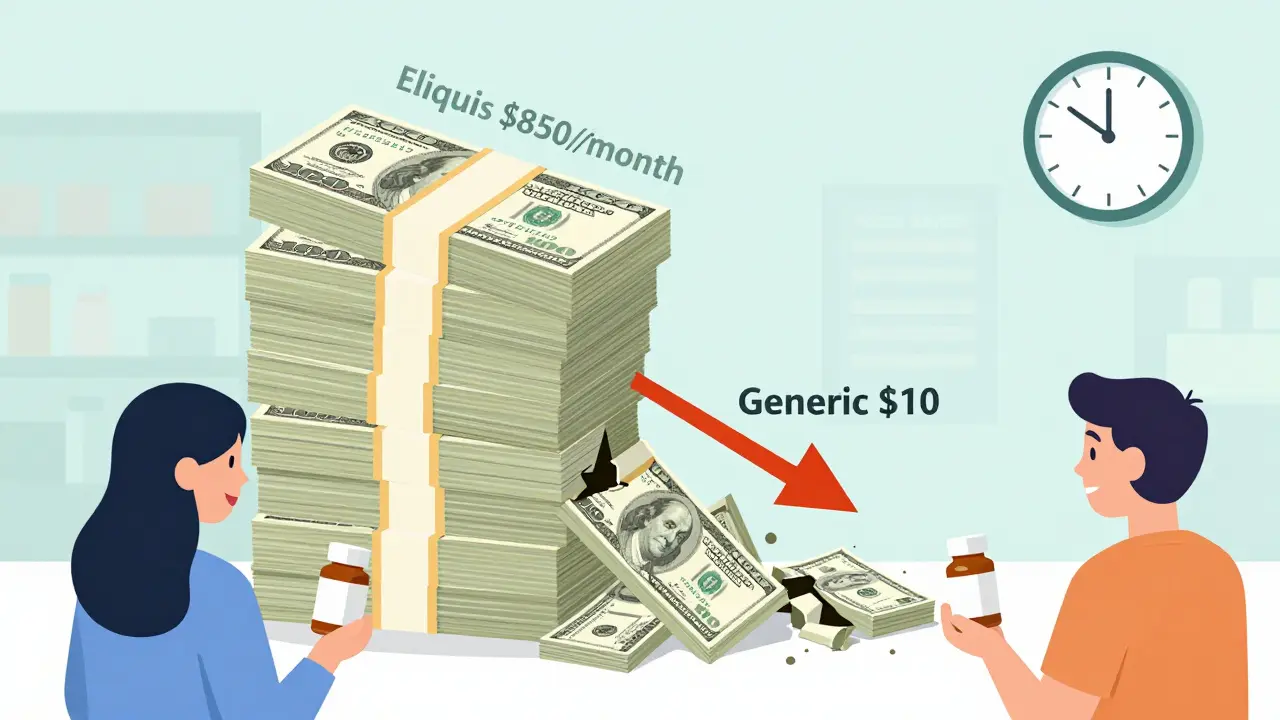

Imagine paying $850 a month for a pill, then suddenly seeing the same pill for $10. That’s not a scam. That’s what happens when a drug’s patent expires. For decades, companies held exclusive rights to sell brand-name medicines like Eliquis, Humira, and Ozempic. They set high prices because no one else could legally make them. But once that patent clock hits zero, everything changes. Generic manufacturers rush in. Prices crash. And patients finally breathe easier.

The science behind this isn’t guesswork. A 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum tracked 505 drugs across eight wealthy countries. In the U.S., prices for brand-name drugs fell 32% in the first year after patent expiration-and by 82% over eight years. In Australia, the drop was 64%. In Switzerland? Just 18%. Why the difference? It’s not about the drug. It’s about the system.

How generic entry turns a monopoly into a marketplace

Patents give drugmakers a legal monopoly-usually 20 years from the date of filing. But the real clock starts ticking when the drug hits the market. By the time it’s approved by the FDA, many patents have already been ticking for years. That’s why some drugs only get 7-12 years of exclusivity before generics can enter.

The first generic version doesn’t always cause a big price drop. Maybe 15-20%. But when the second, third, or fifth generic shows up? That’s when the real squeeze begins. Each new maker needs to undercut the others to win contracts with pharmacies and insurers. The result? Prices spiral down. By year three, if ten or more companies are selling the same pill, you’re looking at 80% off the original price.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2020, when Eliquis (apixaban) lost its patent in the U.S., the first generic hit shelves. Within a year, over 20 companies were making it. Patients who paid $850 monthly for the brand saw their copay drop to $10. Same pill. Same effectiveness. Just a fraction of the cost.

Why some drugs don’t get cheaper-even after patents expire

Not all patent expirations lead to instant savings. Some companies play a different game: patent thickets.

Take Humira (adalimumab). Its main patent expired in 2016. But AbbVie filed over 130 secondary patents-on packaging, dosing schedules, even manufacturing methods. These didn’t protect new science. They just blocked competitors. By the time the first biosimilar, Amjevita, launched in January 2023, Humira had already made $200 billion in sales. Even after biosimilars entered, prices didn’t crash right away. Why? Because insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) were locked into rebate deals with AbbVie. The cheaper drugs were technically available-but not on formularies. Patients still paid high prices because their insurance didn’t cover the generics.

The same thing happened with Ozempic and Wegovy. The base compound’s patent expires in 2026, but the manufacturer has over 140 patents covering formulations, delivery devices, and dosing regimens. Experts at I-MAK say this extends effective exclusivity by 12-14 years beyond the original patent. That’s not innovation. It’s legal obstruction.

Why the U.S. sees bigger drops than other countries

The U.S. doesn’t negotiate drug prices like other rich countries. Medicare can’t haggle. Private insurers do, but only if they have leverage. That’s why the U.S. sees the steepest price drops after patent expiration: because once generics flood in, insurers have no choice but to switch to the cheapest option.

Compare that to Europe. Many countries use reference pricing. If a drug’s generic version costs $10, the government sets the reimbursement rate at $10-even if the brand-name drug still sells for $50. The manufacturer either drops the price or loses market share. No need for 10 competitors to crash the price. One does the job.

In Japan, the government re-prices drugs every two years. In Germany, price negotiations happen at the national level. These systems don’t wait for competition to force prices down. They make it happen.

The U.S. system is reactive. It waits for generics to show up. Then it reacts. That’s why the drop is bigger-but also why patients suffer longer in the high-price years.

What’s holding back cheaper drugs?

It’s not just patents. It’s logistics.

Simple pills? Easy to copy. The FDA approves those in about 10 months. But complex drugs-injectables, inhalers, biologics like Humira-are harder. Making a biosimilar isn’t like copying a pill. It’s like reverse-engineering a living organism. The cost? $2-5 million per product. Fewer companies can afford it. That slows competition.

Then there’s the legal maze. Under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, originator companies and generics must go through a “patent dance”-a series of legal exchanges that can delay entry by two to four years. It’s not designed to speed things up. It’s designed to drag them out.

And even when generics are approved, pharmacists can’t always swap them automatically. In 49 U.S. states, they can substitute a generic for a brand-name drug unless the doctor says “dispense as written.” But for biologics? Rules vary by state. Some require special authorization. Others don’t allow substitution at all.

Patients don’t always know what’s available. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 22% of insured adults didn’t get cheaper generics because their insurance changed their formulary without telling them. They kept paying full price because they didn’t realize a cheaper option existed.

The real winners-and who loses

The biggest winners? Patients. Medicare. Medicaid. Employers paying for employee health plans. In 2023, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $370 billion. That’s $3,000 per person. Over the next decade, the Congressional Budget Office estimates generic and biosimilar competition will save $1.7 trillion.

But who loses? The big drugmakers. Their profits shrink fast after patent expiry. That’s why they spend billions lobbying to extend exclusivity. In 2023, 78% of new patents filed for existing drugs weren’t for new medicines-they were for tweaks. Minor changes. Packaging. Delivery methods. Nothing that made the drug better. Just longer protected.

And let’s not forget the small generic makers. They’re the ones who take the risk. They invest millions to copy a drug, then fight legal battles and wait for approvals. When they finally get in, they’re often bought out by bigger players. The market becomes concentrated again. Competition fades. Prices creep back up.

What’s changing-and what needs to change

There’s hope. In 2023, the FDA approved 870 generic drugs-up 12% from the year before. The agency is now prioritizing complex generics and biosimilars. The European Commission proposed limits on supplementary patents in 2024. The U.S. Patent Office started cracking down on patent thickets in 2023.

But it’s not enough. The average blockbuster drug still gets 10-15 secondary patents. That delays real competition by over four years per drug. The I-MAK report says without reform, patients will wait years longer than they should to get affordable drugs.

What needs to happen? Clearer rules on what counts as a real innovation. Limits on patent extensions. Faster approval for biosimilars. Mandatory substitution laws. And transparency-patients need to know when a cheaper option is available.

Patent expiration isn’t the end of profit. It’s the beginning of fairness. The system was built to reward innovation-not to lock patients into high prices for decades. When the patent runs out, the medicine should become affordable. Not just legally. Actually.

What patients can do right now

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic or biosimilar for this?”

- Check your insurance formulary. If your drug isn’t covered, ask why.

- Use price comparison tools like GoodRx. They show real-time prices for generics.

- If your doctor says “dispense as written,” ask if that’s really necessary. Often, it’s just habit.

- Speak up. Tell your insurer or employer that you want access to cheaper alternatives.

Every dollar saved on drugs is a dollar that can go to rent, food, or a child’s education. Patent expiration isn’t a loophole. It’s the law. And it’s working-when it’s allowed to.

Post A Comment