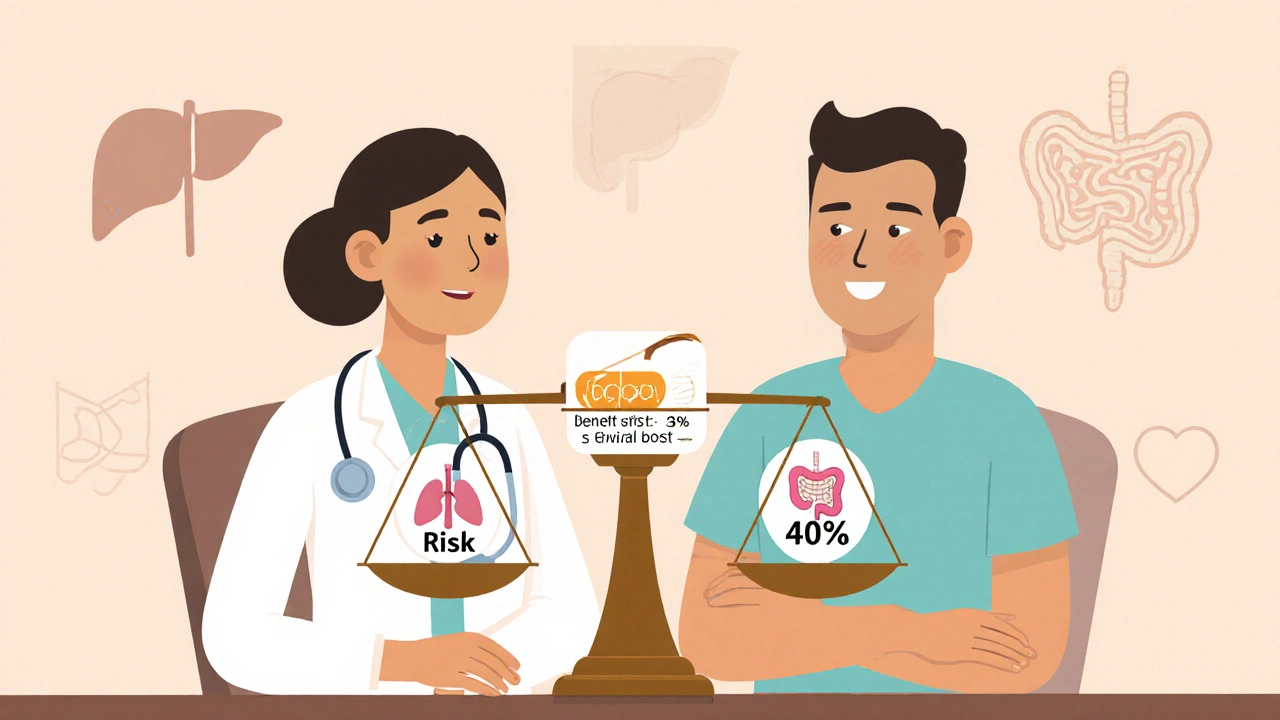

Every time a doctor writes a prescription, they’re not just handing out a pill-they’re making a calculated guess about what’s better: the chance of feeling better or the chance of something going wrong. It’s not about avoiding all risk. It’s about deciding if the benefit is worth the cost. This is called benefit-risk assessment, and it’s the quiet backbone of every medication decision made in clinics, hospitals, and pharmacies around the world.

It’s Not About Eliminating Risk-It’s About Managing It

No medication is risk-free. Even aspirin can cause stomach bleeding. Antibiotics can trigger severe allergic reactions. Chemo can destroy cancer cells but also wipe out healthy ones. So why do we use them at all? Because sometimes, the alternative is worse. Think about a patient with metastatic melanoma. Without treatment, their five-year survival rate is about 10%. With Keytruda, a checkpoint inhibitor, that jumps to 35%. But 40% of patients will face serious immune-related side effects-colitis, liver inflammation, even lung damage. That’s a lot of risk. But for many, it’s a trade-off they’re willing to make. The doctor doesn’t just look at the numbers-they explain them. They say: “This drug gives you a real shot at living longer, but it comes with a high chance of serious side effects. We’ll monitor you closely. What matters most to you?” This isn’t guesswork. It’s a structured process used by regulators like the FDA and doctors in clinics. The FDA’s Benefit-Risk Framework breaks it down into four parts: the condition being treated, what treatments already exist, how well the new drug works, and how dangerous it is. Each piece is weighed against uncertainty. Is the data from a small trial? Are long-term effects unknown? Is this drug meant for someone with a rare disease who has no other options?Context Changes Everything

A drug that’s too risky for a healthy 45-year-old with high blood pressure might be life-saving for a 70-year-old with heart failure and multiple hospitalizations. That’s why context matters more than the drug itself. Take Zolgensma, a gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. It costs $2.1 million. It can cause serious liver damage. But for babies born with this condition, the alternative is progressive muscle loss, inability to breathe, and death before age two. In that context, the price and the risk are accepted. The FDA approved it because the benefit-giving a child a chance to sit up, breathe on their own, live past infancy-outweighed the dangers. On the flip side, a new cholesterol drug might lower heart attack risk by 20%. Sounds great. But if it increases the chance of dangerous bleeding by 1%, regulators hold back. Why? Because the patient population is mostly healthy people with no history of heart disease. The benefit is small. The risk, while rare, is serious. In that case, the scale tips the other way.

Patients and Doctors Don’t Always See Risk the Same Way

Here’s where things get messy. Doctors rely on data. Patients rely on feelings. A 2023 study found that 65% of Parkinson’s patients would accept a 20% risk of involuntary movements (dyskinesia) for a 30% improvement in mobility. Doctors thought patients would only accept a 12% risk. That’s a huge gap. One patient on Reddit refused an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure because they heard about a 0.1% chance of angioedema-a rare but life-threatening swelling of the throat. The doctor knew the drug cut stroke risk by 25%. But the patient heard “swelling in your throat” and couldn’t get past it. That’s how risk perception works. It’s emotional. It’s personal. The FDA now actively collects patient input through initiatives like Patient-Focused Drug Development. In rare disease communities, patients often say: “We’d take a 30% chance of side effects if it means we can walk again.” That’s not irrational-it’s survival. Clinicians used to decide for patients. Now, they decide with them.How Doctors Actually Do This in Practice

It’s not a checklist. It’s a conversation. A primary care doctor spends 15 to 20 minutes per visit explaining risks and benefits, according to a 2022 AMA survey. That’s more time than they spend on most other clinical decisions. They use tools like the FDA’s Patient Decision Aids-simple charts, videos, and analogies. “Imagine 100 people take this pill. Ten might get a rash. But 30 will avoid a heart attack.” But even then, patients misunderstand. A 2023 study found only 35% of people correctly interpret “10% risk” as “1 in 10 chance.” That’s why doctors avoid percentages. They say: “Out of every 10 people like you, one might get this side effect.” They also compare options. For type 2 diabetes, there are eight main drug classes. Some cause weight gain. Others cause diarrhea. One increases heart failure risk. One lowers blood sugar best but costs $800 a month. The doctor doesn’t just pick the most effective. They pick the one that fits the patient’s life: Can they afford it? Do they travel often? Do they hate taking pills? Risk isn’t just medical-it’s personal.

What’s Changing Now

The old way of doing this relied on clinical trials-controlled studies with mostly white, middle-aged, healthy volunteers. But real people aren’t like that. They have other conditions. They take other drugs. They’re older. They’re from different ethnic backgrounds. A 2023 JAMA study found that 75% of trial participants are White, even though minorities make up 40% of the U.S. population. That means we might not fully understand how a drug affects Black, Latino, or Indigenous patients. That’s a dangerous blind spot. Now, regulators are using real-world data-electronic health records, pharmacy logs, patient apps-to see how drugs perform outside the lab. Roche’s ARIA platform uses AI to predict side effects from this data. It’s helped spot liver toxicity signals months earlier than traditional methods. By 2030, experts predict most benefit-risk assessments will be personalized. Instead of “Is this drug safe for most people?” the question will be: “Is this drug safe for you?” Based on your genes, your lifestyle, your other medications, your history. That’s precision medicine-and it’s coming fast.Why This Matters to You

If you’re taking a medication, you’re part of this system. You’re not just a number in a trial. You’re the reason it exists. The next time your doctor says, “This drug has side effects,” don’t just nod. Ask: “What’s the chance I’ll get them? What happens if I don’t take it? Are there other options? What’s the worst that could happen?” You don’t need to be a doctor to understand risk. You just need to know that every pill comes with two sides: one that helps, one that hurts. The job of your provider isn’t to eliminate the hurt. It’s to make sure the help is worth it. The system isn’t perfect. It’s messy, slow, and sometimes inconsistent. But it’s the best we have. And it’s getting better-with data, with patient voices, and with more honesty about what we don’t know.Why do doctors prescribe medications with serious side effects?

Doctors prescribe medications with serious side effects when the potential benefit is significant enough to justify the risk. For example, cancer drugs often cause nausea, hair loss, or immune damage-but without them, survival rates drop dramatically. The decision is based on the severity of the illness, the availability of alternatives, and the patient’s personal goals. A drug that’s too risky for a mild condition may be essential for a life-threatening one.

How do patients’ views on risk differ from doctors’?

Patients often prioritize quality of life over longevity, while doctors focus on clinical outcomes. For instance, Parkinson’s patients are willing to accept a 20% risk of uncontrolled movements if it means a 30% improvement in mobility. Doctors, based on trial data, estimated patients would only accept a 12% risk. Patients with rare diseases are also more likely to accept high risks because they have few or no alternatives. This gap is why patient input is now part of drug approval processes.

Are some medications riskier than others?

Yes. Medications for cancer, autoimmune diseases, and rare conditions typically carry higher risks because they target aggressive or poorly understood diseases. For example, chemotherapy drugs often cause severe side effects but are necessary for survival. In contrast, medications for mild conditions like seasonal allergies or mild hypertension are held to stricter safety standards because the potential benefit is smaller and the population is healthier. Regulatory agencies like the FDA apply different risk thresholds depending on the disease context.

Why do some drugs get approved even when risks aren’t fully known?

Drugs for life-threatening conditions with no alternatives can be approved under accelerated pathways when early data shows strong benefit, even if long-term safety data is limited. About 60% of drugs approved this way have incomplete long-term risk profiles, according to a 2022 JAMA study. These drugs come with strict monitoring requirements-like mandatory blood tests or restricted distribution-to catch problems after approval. The goal is to get life-saving treatments to patients faster, while still managing risk.

How can I make better decisions about my medications?

Ask your provider: What’s the main benefit? How likely is it? What are the most common side effects? How serious are they? Are there alternatives? What happens if I don’t take it? Use simple language: “Out of 10 people like me, how many will see improvement? How many will have a bad reaction?” Don’t be afraid to ask for written materials or patient decision aids. Your input matters-your values should shape the decision, not just the data.

Post A Comment