Polyposis Risk Assessment Tool

This tool helps you assess your personal risk for hereditary polyposis conditions based on your family history and symptoms. It's designed to guide you toward appropriate next steps with a healthcare provider.

Family History Questions

Higher number of affected relatives indicates increased risk.

Earlier diagnosis age increases risk significantly.

Specific symptoms can indicate hereditary forms of polyposis.

Personal Symptoms

Higher number of polyps increases risk of developing cancer.

A cancer diagnosis in your history significantly increases hereditary risk.

Did you know that a single change in your DNA can turn a healthy colon into a field of dozens, even hundreds, of polyps? That’s the reality for people carrying certain gene variants, and it dramatically raises the chance of colon cancer. In this guide we’ll break down how genetics drives polyposis risk, what tests are available, and how you can act on the information.

What is Polyposis?

Polyposis is a condition marked by the growth of multiple polyps in the colon or rectum. Polyps are tiny tissue outgrowths that can be harmless or turn malignant over time. When they appear in large numbers, doctors become concerned because the statistical odds of at least one turning cancerous climb steeply.

Main Types of Polyposis

Not all polyps are created equal, and the genetic underpinnings differ. The three most common hereditary forms are Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), Attenuated FAP (AFAP), and MUTYH‑Associated Polyposis (MAP). Below is a quick snapshot:

| Feature | FAP | AFAP | MAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene involved | APC | APC (often milder mutations) | MUTYH (biallelic) |

| Inheritance | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal recessive |

| Typical # of polyps | >1000 | 20‑100 | 10‑100 |

| Average CRC age | ~39 years | ~45‑50 years | ~50 years |

| Screening start | Age 10‑12 | Age 15‑20 | Age 20‑25 |

How Genetics Determines Your Risk

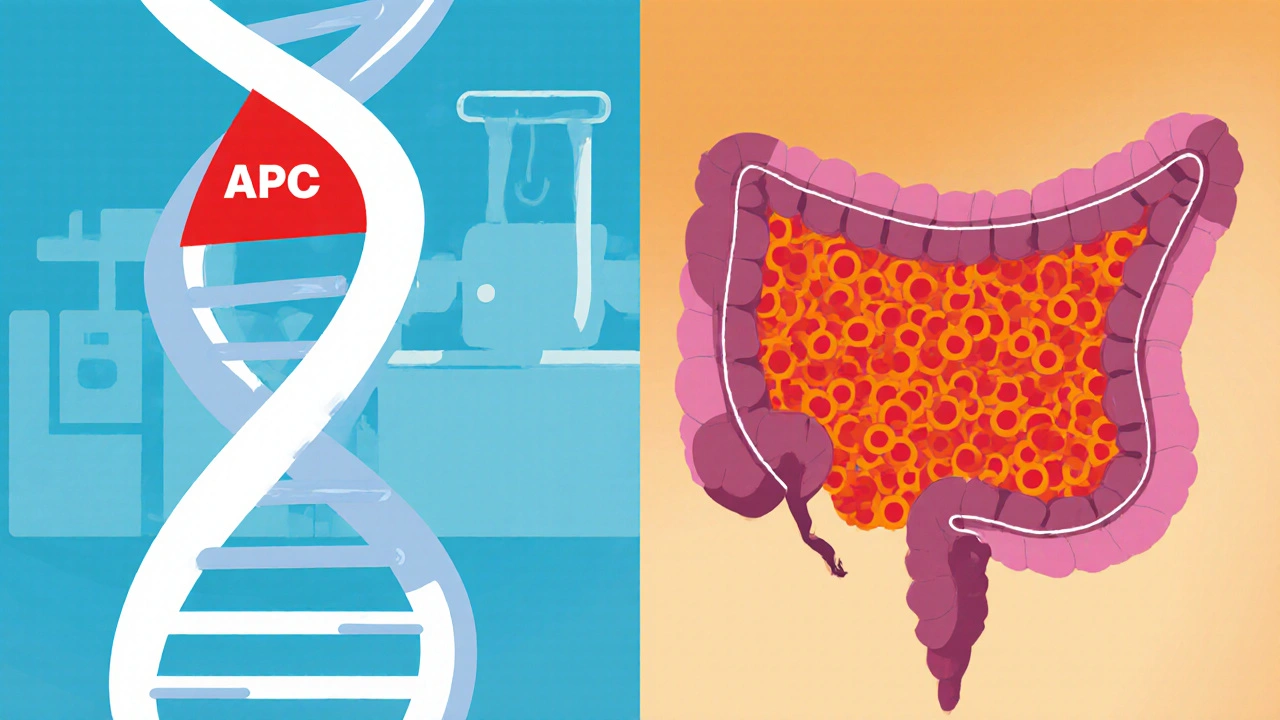

The core of polyposis risk lies in a handful of genes that control how cells grow and repair DNA. The most famous is the APC gene a tumor‑suppressor gene that regulates cell division in the colon. When a pathogenic variant disables APC, the brake on cell growth is released, leading to rapid polyp formation.

Another culprit is the MUTYH gene which helps fix oxidative DNA damage. People who inherit two defective copies (one from each parent) develop MAP. Because MUTYH works on a different repair pathway, MAP tends to produce fewer polyps than classic FAP, but the cancer risk remains significant.

Besides APC and MUTYH, rare variants in DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) can create polyposis‑like phenotypes, often overlapping with Lynch syndrome. The emerging field of polygenic risk scores also shows that dozens of low‑impact variants can combine to push an otherwise “average” person into a higher‑risk bracket.

Inheritance Patterns and What They Mean for Families

Understanding how a gene is passed down helps you gauge who else might be at risk. Autosomal dominant disorders, like FAP, mean a 50 % chance that a child inherits the faulty copy. The condition often shows high penetrance-most carriers develop polyps-though the exact number can vary.

Autosomal recessive conditions, such as MAP, require both parents to carry a carrier‑level mutation. Each child then has a 25 % chance of being affected, a 50 % chance of being a carrier, and a 25 % chance of having two normal copies.

Variable expressivity adds another layer: two siblings with the same APC mutation might have hundreds of polyps while the other has only a few. This makes family history a useful but not foolproof screening tool.

Genetic Testing: Who Should Get Tested and What to Expect

If you or a close relative has been diagnosed with polyposis, genetic testing is the next logical step. Most labs now offer multi‑gene panels that include APC, MUTYH, and the mismatch‑repair genes. Here’s a typical workflow:

- Schedule a pre‑test counseling session with a certified genetic counselor.

- Provide a small blood or saliva sample.

- Lab performs next‑generation sequencing and looks for pathogenic variants.

- Results are reviewed with the counselor, who explains the implications for you and your family.

Testing can reveal a pathogenic APC variant, confirm MAP, or sometimes return a “variant of uncertain significance” (VUS). In the latter case, ongoing research and family studies help reclassify the result over time.

Managing Risk After a Positive Result

Knowing you carry a high‑risk gene is empowering because it unlocks a suite of preventive actions. The cornerstone is regular surveillance:

- Colonoscopy every 1‑2 years starting in early teens for FAP, or in the early twenties for MAP.

- High‑definition imaging or chromoendoscopy to catch flat lesions that standard scopes might miss.

When polyps become numerous or large, many doctors recommend a prophylactic colectomy-removing the colon before cancer develops. The procedure can be total (removing the entire colon) or partial, depending on polyp burden and patient preference.

Beyond surgery, lifestyle tweaks-high fiber diet, regular exercise, limiting red meat and alcohol-can modestly lower risk, though they don’t replace surveillance.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

Scientists are now exploring polygenic risk scores that combine dozens of small‑effect variants to fine‑tune individual risk estimates. Early studies suggest that adding a polygenic score to an APC test can better predict who will develop cancer earlier.

Gene‑editing tools like CRISPR are being tested in mouse models to repair APC mutations directly. While human trials are years away, the concept hints at a future where we might correct the root cause instead of managing its downstream effects.

Finally, long‑term registries that track outcomes of different surgical approaches are helping clinicians personalize the choice between total colectomy, ileorectal anastomosis, or watchful waiting.

Key Takeaways

- Polyposis is a genetically driven condition; APC and MUTYH are the primary culprits.

- Inheritance can be autosomal dominant (FAP) or recessive (MAP), influencing family testing strategies.

- Multi‑gene testing and genetic counseling are essential for accurate risk assessment.

- Regular colonoscopic surveillance and, when needed, prophylactic surgery dramatically lower colorectal cancer mortality.

- Research into polygenic risk scores and gene editing promises more precise prevention in the next decade.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a person with a single APC mutation avoid surgery?

Surgery is often recommended when polyps exceed 20-30 or show dysplasia. Some individuals with few, well‑controlled polyps can defer surgery with intensive colonoscopic monitoring, but the decision is highly individualized.

Is genetic testing covered by insurance?

Many insurers cover testing when there is a documented family history of polyposis or early‑onset colorectal cancer. Pre‑authorization and a referral from a gastroenterologist or genetic counselor are usually required.

What is the difference between FAP and attenuated FAP?

Classic FAP typically produces >1,000 polyps and cancer before age 40, while attenuated FAP (AFAP) yields 20‑100 polyps, with cancer often appearing in the late 40s or 50s. The genetic mutations are in the same APC gene but differ in location and effect.

Do lifestyle changes affect polyposis risk?

Lifestyle tweaks can lower overall colorectal cancer risk, but they won’t stop polyps caused by high‑risk gene mutations. They are best used as complementary measures alongside medical surveillance.

What is a VUS and how should it be handled?

A Variant of Uncertain Significance (VUS) is a genetic change whose impact on disease risk isn’t yet known. Experts monitor new research, re‑classify the variant when evidence emerges, and may recommend screening based on family history in the meantime.

Post A Comment