Parkinson's Psychosis: Causes, Risks, and What You Need to Know

When someone with Parkinson’s starts seeing things that aren’t there—like people in the room or animals on the floor—it’s not imagination. It’s Parkinson’s psychosis, a neuropsychiatric condition that develops in up to 50% of people with advanced Parkinson’s disease, often involving visual hallucinations and delusions. Also known as Parkinson’s disease psychosis, it’s not a mental illness on its own, but a direct result of brain changes from the disease and the medications used to treat it.

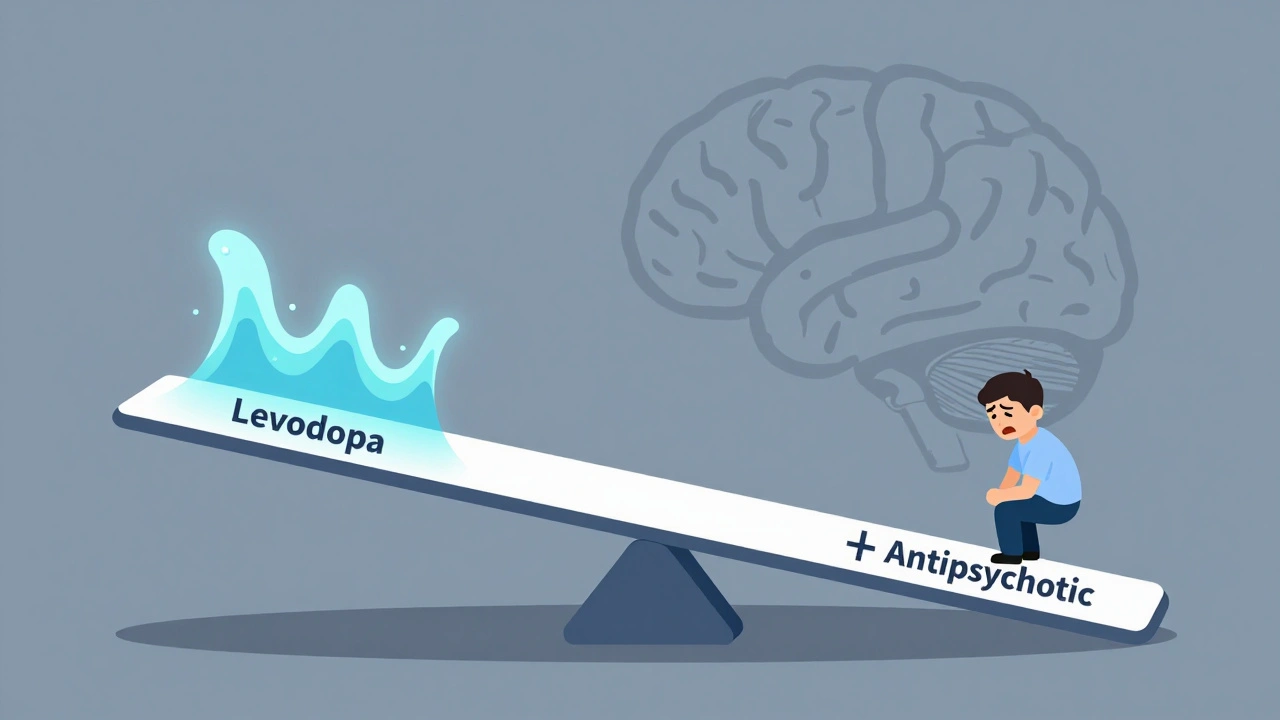

This isn’t just about seeing things. People may believe their spouse is cheating, that someone is stealing from them, or that they’re being followed. These aren’t random thoughts—they’re symptoms tied to dopamine imbalances, loss of visual processing control, and the long-term use of Parkinson’s drugs like levodopa. What makes it tricky is that the very medications helping movement can make psychosis worse. And if doctors aren’t careful, treating the hallucinations with standard antipsychotics can shut down movement entirely, leaving the person even more disabled.

Antipsychotics for Parkinson’s, specialized drugs like pimavanserin and clozapine that target hallucinations without worsening motor symptoms. Also known as Parkinson’s-specific antipsychotics, these are the only safe options. Regular antipsychotics like haloperidol? Avoid them. They block dopamine too broadly and can cause sudden stiffness, falls, or even death in Parkinson’s patients. Then there’s dementia with Lewy bodies, a closely related condition that shares the same brain plaques as Parkinson’s and often includes similar psychotic symptoms. Also known as Lewy body dementia, it’s not a different disease—it’s the same process, just starting in different parts of the brain. Many people with Parkinson’s psychosis are actually on the spectrum of this broader disorder.

It’s not just about drugs. Sleep problems, infections, vision loss, and even dehydration can trigger or worsen these episodes. A simple urinary tract infection can send someone into a full-blown psychotic state. That’s why checking for basic medical issues is often the first step—before reaching for stronger meds.

What you’ll find in the articles below isn’t just theory. It’s real-world advice from people who’ve lived through this, and from doctors who’ve learned the hard way what works and what doesn’t. You’ll see how medication changes can calm hallucinations without freezing movement, why some supplements might make things worse, and how to spot early signs before they spiral. There’s no one-size-fits-all fix, but there are clear, practical steps you can take right now to reduce risk, improve safety, and keep life more manageable—for the person with Parkinson’s and for their caregivers.

Levodopa and Antipsychotics: How Opposing Dopamine Effects Worsen Symptoms

Levodopa and antipsychotics have opposing effects on dopamine, making it dangerous to use them together. This article explains how this interaction worsens symptoms in Parkinson’s and schizophrenia, and what newer treatments are doing to solve it.

Read More